Key takeaways

- Virtual screening computationally filters millions to billions of compounds down to a testable subset, achieving hit rates of 1–40% compared to 0.01–0.14% for experimental high-throughput screening.

- Two main approaches exist: structure-based (using protein 3D structure and docking) and ligand-based (using known active compounds as templates).

- Ultra-large virtual screening now routinely screens 10⁹+ compounds, enabled by GPU acceleration, cloud computing, and AI methods up to 10 million times faster than traditional docking.

- Recent breakthroughs like DrugCLIP have enabled genome-wide screening of 10,000 protein targets against 500 million compounds in a single day.

What is virtual screening?

Virtual screening (VS) is a computational technique used in drug discovery to search large libraries of small molecules and identify those most likely to bind to a biological target. Rather than physically testing every compound, researchers use computer simulations to predict which molecules are worth synthesizing and testing experimentally.

A virtual screening campaign typically answers: Which compounds from a library of millions should we prioritize for experimental testing?

By filtering compounds that are unlikely to bind or have poor drug-like properties, virtual screening improves the "enrichment factor"—the proportion of active compounds in the final selection compared to random picking.

Typical hit rates from experimental high-throughput screening (HTS) range from 0.01% to 0.14%, while prospective virtual screening achieves hit rates of 1% to 40%.

Types of virtual screening

Virtual screening methods fall into two main categories.

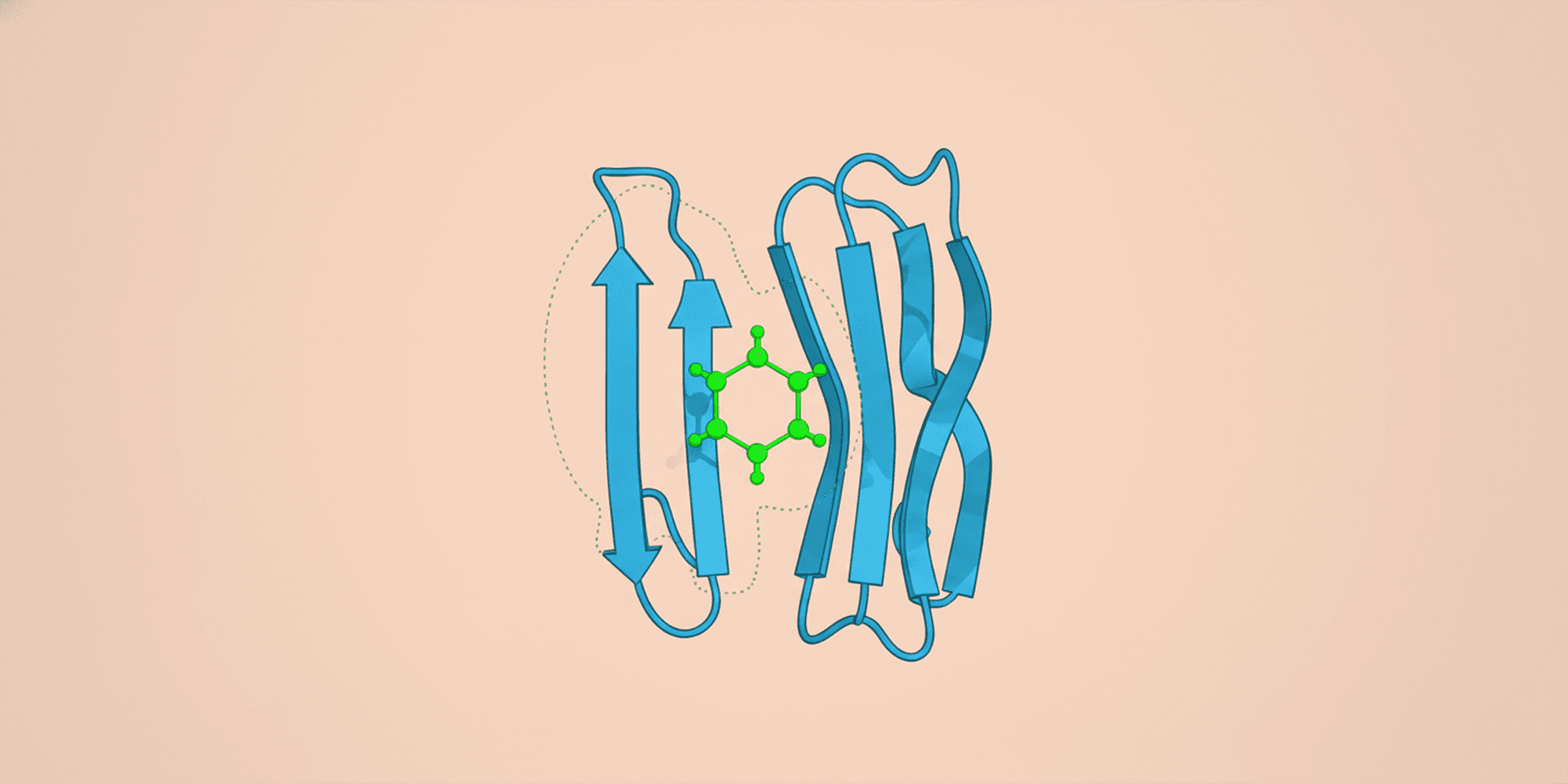

Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS)

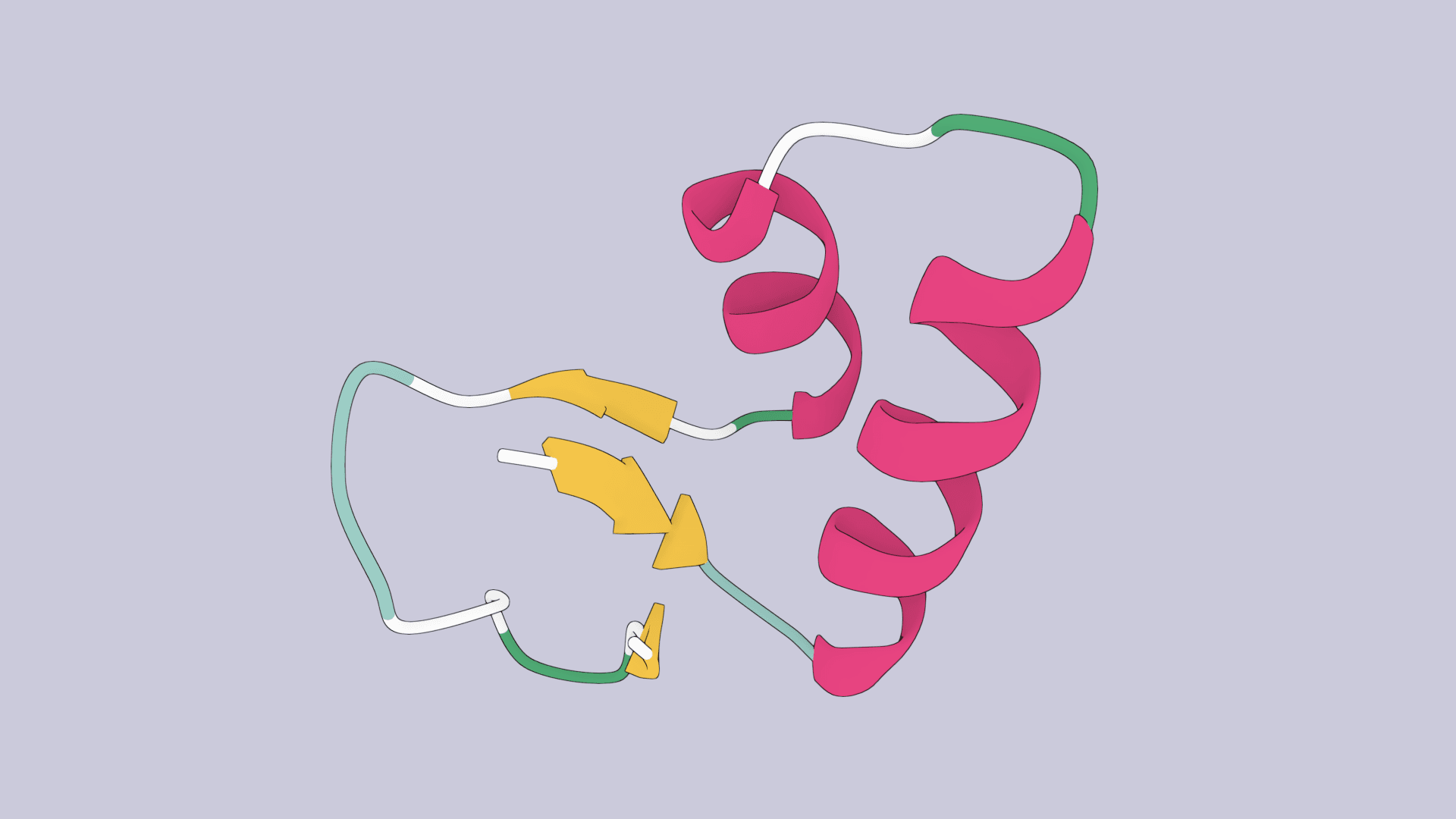

When the 3D structure of the target protein is known (from X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or prediction via AlphaFold 2), structure-based methods simulate how ligands might bind. The core technique is molecular docking: each compound is placed into the binding site in multiple orientations while a scoring function estimates binding affinity.

Common SBVS tools include AutoDock Vina, GNINA, DiffDock, Smina, and AutoDock-GPU. For protein-protein docking, HADDOCK3 and ColabDock are popular.

Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS)

When the protein structure is unavailable, ligand-based methods use known active compounds as templates. These rely on the principle that molecules with similar structures tend to have similar biological activities. Key approaches include molecular similarity searches, pharmacophore modeling, and QSAR models using molecular descriptors.

Hybrid approaches

The most effective campaigns combine both: ligand-based methods filter billions to millions of compounds, then structure-based docking reduces millions to thousands, followed by ADMET filtering to select hundreds for testing.

AI-powered virtual screening

Artificial intelligence has transformed virtual screening. Deep learning methods now achieve speeds and accuracies impossible with traditional docking.

Embedding-based methods like DrugCLIP and SPRINT represent proteins and ligands as vectors in shared space, enabling screening speeds up to 10 million times faster than docking. SPRINT can query the human proteome against 6.7 billion compounds in 16 minutes.

Neural network scoring with tools like GNINA uses CNNs to score poses, often outperforming classical scoring functions. DiffDock uses diffusion models for binding pose prediction.

Flexible docking tools like DynamicBind model protein conformational changes during binding—a key limitation of rigid docking.

Ultra-large library screening

Modern virtual screening operates at unprecedented scale. ZINC-22 contains 37 billion make-on-demand molecules; Enamine REAL has 6.7+ billion synthetically accessible compounds.

Platforms like VirtualFlow have demonstrated billion-compound screening, docking 1.3 billion compounds in ~15 hours on cloud infrastructure. GPU-accelerated tools like AutoDock-GPU and AI pre-filters make large-scale screening accessible without specialized hardware.

Running a virtual screen

A successful campaign requires careful preparation at each stage.

- Target preparation: Obtain a reliable structure from the Protein Data Bank or predict with AlphaFold 2, ESMFold, or Boltz-2. Use PDB Fixer to fix missing residues and PROPKA for protonation states. Identify binding sites with FPocket or PocketFlow.

- Library preparation: Filter compounds using Lipinski's Rule of 5, Veber's Rule, and PAINS Filter to remove problematic structures.

- Protocol validation: Re-dock known ligands to verify the setup reproduces experimental poses (RMSD < 2.0 Å).

- Post-screening: Inspect poses in PDB Viewer, apply ADMET AI and toxicity prediction filters, then validate top hits experimentally.

Applications

Virtual screening has applications throughout drug discovery:

- Hit identification: Filter millions of compounds to find binders

- Lead optimization: Screen analogs to improve affinity and selectivity

- Drug repurposing: Screen approved drugs against new targets

- Off-target identification: Reverse screening predicts unintended binding

- Mechanism studies: Screen against protein panels to identify targets

Limitations

Virtual screening remains predictive, not definitive.

Scoring accuracy: Traditional scoring functions have ~2–3 kcal/mol error and correlate weakly with experimental affinities. They distinguish binders from non-binders but struggle to rank similar compounds.

False positives/negatives: Hit rates of 1–10% mean 90–99% of predicted hits fail validation. No screen is perfect.

Beyond binding: VS predicts binding, not biological activity. A compound might bind tightly but fail to modulate function, permeate cells, or avoid toxicity. ADMET AI helps assess these properties.

FAQs

What is the difference between virtual screening and high-throughput screening?

High-throughput screening (HTS) physically tests compounds in assays; virtual screening computationally predicts binders. VS achieves hit rates of 1–40% vs 0.01–0.14% for HTS. Modern drug discovery uses VS to filter libraries before HTS validation.

How accurate is virtual screening?

Structure-based screens achieve 1–10% hit rates on average, with AI methods reaching 15–33% in validated studies. Pose prediction succeeds ~70–80% of the time within 2 Å of experimental structures.

Which method should I use?

- Have a protein structure? Use AutoDock Vina or GNINA

- Known actives but no structure? Use ligand-based similarity search

- Need flexibility? Use DynamicBind

- Screening thousands quickly? Use SPRINT

What's the difference between docking and virtual screening?

Molecular docking predicts how one ligand binds to a protein. Virtual screening applies docking at scale to search entire libraries.