Key takeaways

- ADMET stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity—the properties that determine whether a molecule that binds its target can actually become a drug.

- Poor ADMET properties cause 40–50% of clinical trial failures, more than lack of efficacy.

- Early ADMET screening reduced pharmacokinetic failures from ~40% (1991) to ~10% (2000), but toxicity failures increased over the same period.

- Machine learning tools like ADMET-AI now predict 50–175 endpoints from molecular structure, enabling filtering before synthesis.

In the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies had a problem: approximately 40% of drug candidates were failing in clinical trials due to poor pharmacokinetics. Compounds that looked promising in cell assays and animal models were reaching humans only to be rapidly metabolized, poorly absorbed, or unable to reach their targets. Each late-stage failure cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

The industry's make-do solution was to "fail fast, fail cheap"—measure ADMET properties as early as possible and kill doomed compounds before investing in expensive development. And it worked, with pharmacokinetic failures dropping to roughly 10% by 2000.

But over the same period toxicity failures rose from 20% to 30%. The compounds surviving early ADMET screens were now failing because they damaged livers, disrupted heart rhythms, or caused other safety issues. The "T" in ADMET became just as important as the other four letters.

Today, combined ADMET-related failures still account for roughly half of all drug attrition. Understanding these properties isn't optional but it's the difference between a molecule that binds a target and one that actually treats patients.

What ADMET actually is?

AMDET is an acronym that stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. ADMET tracks what happens to a drug from the moment it enters the body until it's eliminated. Each letter represents a distinct question:

- Absorption: Can the drug get into the bloodstream? For oral drugs, this means crossing the intestinal wall. A compound might be incredibly potent in a test tube but worthless if it can't survive stomach acid or pass through gut membranes.

- Distribution: Where does the drug go once it's absorbed? Some compounds bind tightly to blood proteins and never reach tissues. Others cross into the brain when they shouldn't (causing side effects) or fail to cross when they should (for CNS drugs). The volume of distribution tells you whether a drug stays in blood or spreads throughout the body.

- Metabolism: How does the body chemically modify the drug? The liver's cytochrome P450 enzymes transform most drugs into different molecules (metabolites). Sometimes this inactivates the drug. Sometimes it activates a prodrug. Sometimes it creates toxic byproducts. A drug metabolized too quickly requires frequent dosing; one metabolized too slowly accumulates dangerously.

- Excretion: How does the drug leave the body? Primarily through kidneys (urine) or liver (bile/feces). Half-life—the time for blood concentration to drop by half—determines dosing schedules. A drug with a 2-hour half-life needs multiple daily doses; one with a 24-hour half-life might work once daily.

- Toxicity: Does the drug cause harm? This encompasses everything from mild side effects to organ damage. Key concerns include liver toxicity (DILI), heart rhythm disruption (hERG channel inhibition), DNA damage (mutagenicity), and cancer risk (carcinogenicity).

The CYP problem

One enzyme family dominates drug metabolism: the cytochrome P450s (CYPs). Five isoforms—CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4—metabolize over 75% of all marketed drugs. CYP3A4 alone handles roughly 50%.

This concentration creates two problems:

- Drug-drug interactions: If two drugs compete for the same CYP enzyme, one can inhibit the other's metabolism. Blood levels of the affected drug spike, potentially causing toxicity. Grapefruit juice famously inhibits CYP3A4, which is why some medications carry warnings about it.

- Genetic variation: CYP enzymes vary between individuals. Some people are "poor metabolizers" for CYP2D6—a standard dose becomes an overdose. Others are "ultra-rapid metabolizers"—drugs clear too fast to work. Pharmacogenomics tries to match doses to individual genetics, but most drugs are still prescribed one-size-fits-all.

Predicting CYP interactions early lets medicinal chemists modify structures to avoid problematic metabolism. ADMET-AI predicts both CYP inhibition (will this drug affect other drugs?) and CYP substrate status (will this drug be affected by CYP-metabolizing inhibitors or inducers?).

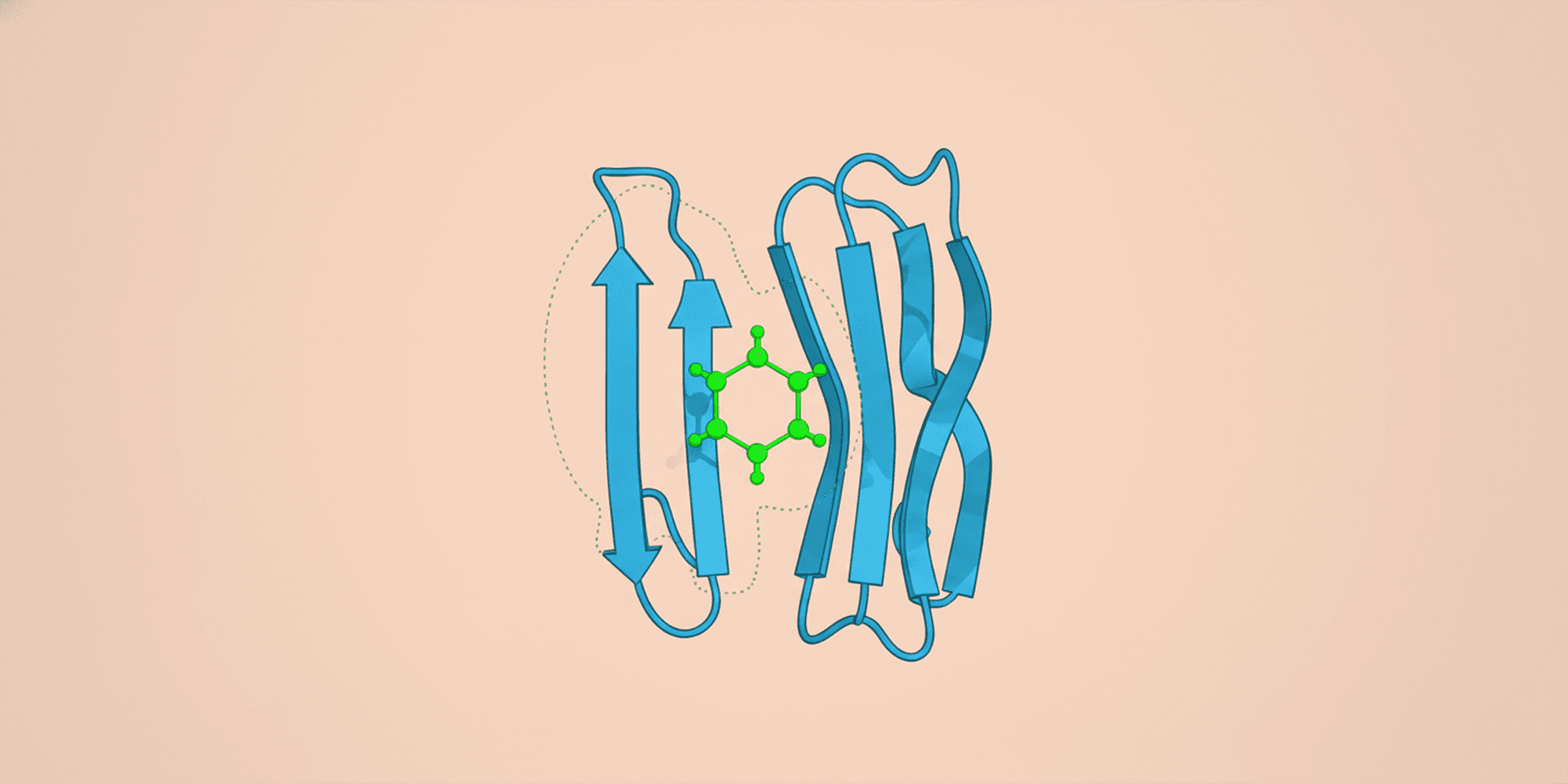

Simple rules vs. comprehensive prediction

Lipinski's Rule of Five

In 1997, Christopher Lipinski analyzed ~2,500 clinical compounds and found that poor oral absorption correlates with four molecular properties. The Rule of Five flags compounds where:

- Molecular weight > 500 Da

- LogP > 5 (too lipophilic)

- Hydrogen bond donors > 5

- Hydrogen bond acceptors > 10

The rule is a quick filter, not a prediction. Plenty of successful drugs violate it (especially natural products and antibiotics), and plenty of rule-compliant compounds fail for other reasons. It catches the obvious losers but misses subtler problems.

Veber's Rule

Veber's Rule adds two criteria for oral bioavailability:

- Rotatable bonds ≤ 10

- Polar surface area ≤ 140 Ų

Flexible molecules with many rotatable bonds pay an entropic penalty when binding—they lose conformational freedom. High polar surface area reduces membrane permeability.

Why rules aren't enough

A compound can pass Lipinski and Veber but still fail because it:

- Inhibits hERG channels (cardiotoxicity)

- Is rapidly glucuronidated (poor half-life)

- Forms reactive metabolites (hepatotoxicity)

- Is a P-glycoprotein substrate (effluxed from cells)

Comprehensive ADMET prediction examines dozens of specific endpoints, not just a few molecular properties. Modern ML models trained on experimental data capture patterns that simple rules miss.

Machine learning changes the game

Traditional ADMET relied on experimental assays—Caco-2 cells for permeability, liver microsomes for metabolic stability, hERG patch clamp for cardiotoxicity. These assays are accurate but expensive and slow. Testing 1,000 compounds might take weeks and cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Machine learning models trained on historical assay data can now predict many ADMET endpoints from molecular structure alone:

| Endpoint | Typical ML Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Human intestinal absorption | 91–99% |

| Blood-brain barrier penetration | R² ~0.98 |

| CYP inhibition | 95–98% |

| Metabolic stability | ~93% |

| Ames mutagenicity | 85–90% |

| Hepatotoxicity | 75–82% |

Absorption and distribution predictions are generally strong because the underlying physics (membrane permeability, protein binding) is relatively simple. Toxicity predictions are harder—multiple mechanisms, sparse data, and complex biology conspire against accuracy.

The practical value isn't perfect prediction but improved prioritization. If ML filters reduce experimental testing from 10,000 compounds to 500 while keeping most of the good ones, that's a massive efficiency gain—even if some predictions are wrong.

Key platforms

ADMET-AI on ProteinIQ predicts comprehensive profiles from SMILES strings: physicochemical properties, absorption (HIA, Caco-2, PAMPA, P-gp), distribution (BBB, protein binding, volume of distribution), metabolism (CYP inhibition and substrates), excretion (half-life, clearance), and toxicity (Ames, DILI, hERG, carcinogenicity, LD50).

ADMETlab 3.0 is a widely-used web server with 88 endpoints and decision support features. It's been visited over 1.7 million times and cited nearly 1,000 times.

SwissADME provides free physicochemical and pharmacokinetic predictions with good drug-likeness assessment.

Integrating ADMET into drug discovery

ADMET filtering slots naturally into the virtual screening workflow:

After docking: Molecular docking identifies compounds that might bind the target. ADMET filters remove those unlikely to become drugs:

- Apply Lipinski and Veber rules as coarse filters

- Remove compounds with structural liabilities using PAINS and Brenk filters

- Run comprehensive ADMET-AI predictions

- Flag specific issues (hERG liability, CYP inhibition, low solubility)

- Prioritize compounds with balanced profiles for synthesis

During optimization: As medicinal chemists modify hit compounds, ADMET predictions guide decisions. Adding a methyl group might improve potency but worsen metabolic stability. Predictions help anticipate trade-offs before synthesis.

Before candidate selection: Final candidates need acceptable ADMET profiles for their indication. A CNS drug must cross the blood-brain barrier; an anti-infective targeting the gut might deliberately avoid absorption. Context matters.

The optimization trap

ADMET properties are interconnected in frustrating ways. Improving one often worsens another:

Solubility vs. permeability: Adding polar groups improves aqueous solubility but reduces membrane permeability. Too polar and the compound can't cross into cells; too lipophilic and it won't dissolve.

Metabolic stability vs. clearance: Blocking metabolic soft spots (hydroxylation sites) increases half-life but might reduce clearance so much that the drug accumulates.

Potency vs. selectivity: Highly lipophilic compounds often bind targets tightly but also bind many off-targets, increasing toxicity risk.

Size vs. everything: Larger molecules tend to be more potent (more binding contacts) but worse for absorption, distribution, and metabolism. The "molecular obesity" of modern drug candidates is a recognized problem.

Medicinal chemists spend careers learning to navigate these trade-offs. There's no universal optimum—the right ADMET profile depends on the target, indication, and route of administration.

What predictions can't tell you

ADMET prediction has real limitations:

Applicability domain: Models perform poorly on molecules structurally different from their training data. Novel scaffolds may get unreliable predictions.

Mechanism blindness: ML models learn correlations, not mechanisms. They can't explain why a compound might be hepatotoxic, limiting guidance for optimization.

Context dependence: Predictions assume standard conditions. Actual ADMET depends on formulation, dose, fed/fasted state, comedications, and patient-specific factors.

Rare events: Idiosyncratic toxicity affecting 1 in 10,000 patients can't be predicted from structure. These events only emerge in large clinical trials or post-marketing surveillance.

Metabolite effects: Predictions typically evaluate parent compounds. If a metabolite causes toxicity (as with acetaminophen's NAPQI), parent-only prediction misses it.

The right mindset: predictions are hypotheses that improve prioritization. They don't replace experimental validation—they reduce how much validation you need.

FAQs

What's the difference between ADME and ADMET?

ADME covers pharmacokinetics: how the body handles a drug. ADMET adds toxicity: whether the drug harms the body. The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but ADMET better reflects that safety failures are as important as pharmacokinetic failures.

Why can't you just measure ADMET experimentally?

You can, and you should for advanced candidates. But experimental ADMET profiling costs dollars to tens of dollars per compound and takes days to weeks. When screening millions of compounds, computational prediction (pennies per compound, milliseconds per compound) is the only practical first filter.

Which ADMET property causes the most failures?

It depends on the era. In the 1990s, poor pharmacokinetics (especially bioavailability) dominated. Today, toxicity—particularly hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity—causes more failures because early pharmacokinetic screening successfully eliminates PK-challenged compounds.

Can ADMET properties be optimized?

Yes, through medicinal chemistry. Adding polar groups improves solubility. Blocking metabolic sites extends half-life. Removing hERG-binding motifs reduces cardiac risk. But optimizing one property often worsens others, requiring careful balancing.

How accurate are computational ADMET predictions?

It varies by endpoint. Physicochemical properties are calculated exactly. Absorption predictions typically achieve 85–95% accuracy. Toxicity predictions are less reliable (75–85%) because mechanisms are complex and training data is limited. Use predictions for prioritization, not definitive answers.

References

-

Kola, I., Landis, J. (2004). Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 3, 711-715. DOI

-

Lipinski, C.A. et al. (1997). Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 23(1-3), 3-25. DOI

-

Veber, D.F. et al. (2002). Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 45(12), 2615-2623. DOI

-

Xiong, G. et al. (2021). ADMETlab 2.0: an integrated online platform for accurate and comprehensive predictions of ADMET properties. Nucleic Acids Research, 49(W1), W5-W14. DOI

-

Swanson, K. et al. (2024). ADMET-AI: a machine learning ADMET platform for evaluation of large-scale chemical libraries. Bioinformatics, 40(7), btae416. DOI

-

van de Waterbeemd, H., Gifford, E. (2003). ADMET in silico modelling: towards prediction paradise? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2, 192-204. DOI