What is AutoDock Vina?

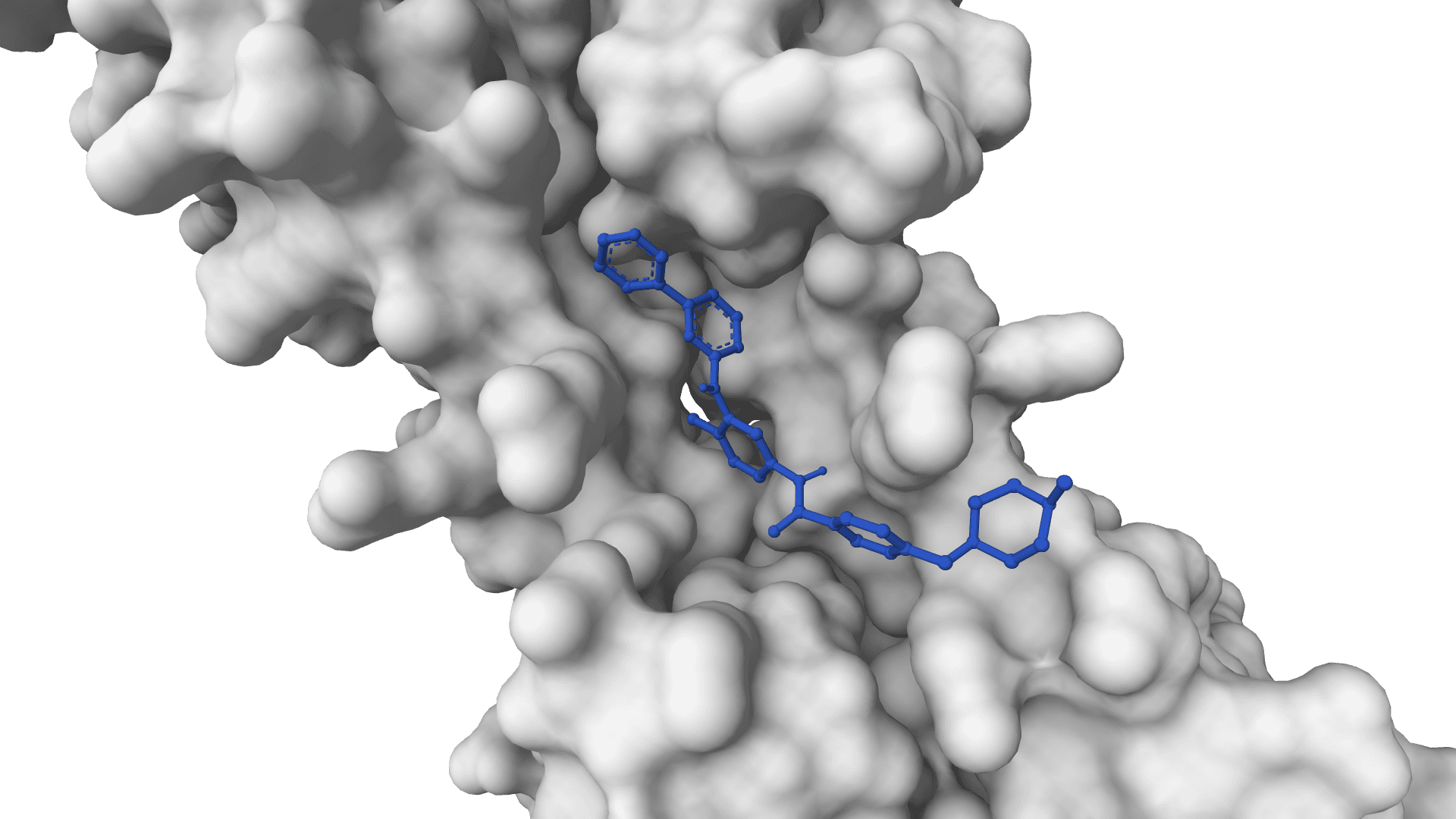

AutoDock Vina is an open-source molecular docking program for predicting how small molecules (ligands) bind to proteins. Developed by Oleg Trott and Arthur Olson at the Scripps Research Institute, Vina predicts the preferred orientation (binding mode) of a ligand within a protein binding site and estimates the strength of that interaction (binding affinity) in kcal/mol.

Molecular docking is fundamental to structure-based drug discovery. By computationally screening large compound libraries against protein targets, researchers can identify promising drug candidates before expensive experimental validation. AutoDock Vina achieves approximately two orders of magnitude speed-up compared to its predecessor, AutoDock 4, while improving accuracy—making it one of the most widely used docking programs in computational chemistry.

How to use AutoDock Vina online

ProteinIQ provides a web-based interface for running AutoDock Vina without command-line installation or file format conversion. Upload a protein structure, provide a ligand, adjust docking parameters, and receive ranked binding poses with 3D visualization.

Inputs

| Input | Description |

|---|---|

Protein (Receptor) | The target protein structure. Upload a PDB file (.pdb, .ent) or enter a 4-letter PDB ID (e.g., 1HSG) to fetch from RCSB. The structure should ideally have water molecules and co-crystallized ligands removed. |

Ligand | The small molecule to dock. Enter a SMILES string directly (e.g., CCO for ethanol), upload a file (.pdbqt, .sdf, .mol, .smiles), or enter a PubChem CID to fetch the structure. Metal-containing ligands are not supported—use GNINA instead. |

Job name | Optional identifier for the docking job. Helps organize results when running multiple docking experiments. |

Settings

Docking parameters

| Setting | Description |

|---|---|

Scoring function | Algorithm for estimating binding affinity. Vina (default) is fast and accurate for most cases. Vinardo offers improved virtual screening performance. AutoDock4 is better for metalloproteins but requires flexible residues. |

Exhaustiveness | Number of independent docking runs (1–32, default 8). Higher values increase the chance of finding the optimal pose but scale runtime linearly. Use 16–32 for publication-quality results. |

Number of poses | Maximum binding poses to generate (1–20, default 9). More poses provide better coverage of potential binding modes. |

Advanced settings

| Setting | Description |

|---|---|

Energy range | Maximum energy difference from best pose in kcal/mol (1–10, default 3). Only poses within this range of the top-scoring mode are returned. Increase to capture more alternative binding modes. |

Min RMSD between poses | Minimum structural difference between poses in Ångströms (0.5–3.0, default 1.0). Lower values allow more similar poses; higher values enforce diversity. |

Configure search space | Toggle to manually define the docking search box. When disabled, the entire protein is searched automatically. |

Search mode | When search space is configured: Auto searches the whole protein; Manual allows specifying exact coordinates. |

Center X/Y/Z | Center coordinates of the search box in Ångströms. Only visible in manual search mode. Use coordinates from a known binding site or co-crystallized ligand. |

Size X/Y/Z | Dimensions of the search box in Ångströms (10–50, default 25). Smaller boxes search faster but must fully contain the binding site. Keep total volume under 27,000 ų (30×30×30) unless increasing exhaustiveness. |

Flexible residues | Comma-separated list of residues to make flexible during docking (e.g., A:ARG120,A:TYR135). Allows induced-fit modeling but increases runtime. Required when using AutoDock4 scoring. |

Random seed | Integer for reproducible results. Set to 0 for random initialization, or use a specific value to replicate docking runs exactly. |

CPU cores | Number of parallel threads (1–8, default 4). More cores reduce runtime but consume additional compute resources. |

Results

The docking output includes a ranked list of binding poses and an interactive 3D viewer.

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

Mode | Pose rank, where 1 represents the predicted best binding mode based on affinity score. |

Affinity (kcal/mol) | Predicted binding free energy. More negative values indicate stronger binding. Typical drug-like compounds range from −5 to −12 kcal/mol. |

File | Downloadable PDBQT file containing the docked ligand coordinates for each pose. |

Interpreting affinity scores

Binding affinity predictions have a standard error of approximately 2.85 kcal/mol. As a rough guide:

- < −10 kcal/mol: Very strong binding (sub-nanomolar affinity)

- −7 to −10 kcal/mol: Strong binding (nanomolar range)

- −5 to −7 kcal/mol: Moderate binding (micromolar range)

- > −5 kcal/mol: Weak binding

These values are most useful for ranking compounds against the same target rather than predicting absolute affinities.

How does AutoDock Vina work?

AutoDock Vina combines an empirical scoring function with a global optimization algorithm to predict protein-ligand binding. The program evaluates millions of ligand conformations within a defined search space, scoring each pose and refining promising candidates to find the lowest-energy binding modes.

Scoring function

The Vina scoring function evaluates protein-ligand interactions by summing pairwise atomic contributions. Inspired by the X-Score function, Vina uses an empirical approach trained on the PDBbind database of experimentally determined binding affinities.

Energy terms

The scoring function combines five interaction terms, each weighted by coefficients optimized through machine learning:

| Term | Weight | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gauss1 | −0.0356 | Short-range attractive steric interaction |

| Gauss2 | −0.00516 | Long-range attractive steric interaction |

| Repulsion | 0.840 | Van der Waals repulsion when atoms overlap |

| Hydrophobic | −0.0351 | Favorable interactions between hydrophobic atoms |

| Hydrogen bond | −0.587 | Favorable hydrogen bonding interactions |

An additional entropy penalty of 0.0585 kcal/mol per rotatable bond accounts for the loss of conformational freedom upon binding. All atomic interactions are cut off at 8 Å to improve computational efficiency.

Scoring function variants

- Vina: The default scoring function. Fast and accurate for most drug-like molecules. Best choice for general-purpose docking.

- Vinardo: An alternative empirical function with the long-range Gaussian term removed and modified atomic radii. Shows improved virtual screening performance in benchmarks.

- AutoDock4: The classical force field from AutoDock 4. Better suited for metalloproteins and systems where metal coordination is important. Requires specifying flexible residues.

Optimization algorithm

Vina employs an iterated local search global optimizer combining stochastic global exploration with deterministic local refinement.

Search process

The algorithm proceeds through repeated cycles:

- Mutation: Random perturbation of ligand position, orientation, and torsion angles

- Local optimization: Gradient-based refinement using the BFGS quasi-Newton method

- Acceptance: Metropolis criterion determines whether to accept or reject the new conformation

Multiple independent runs start from random initial configurations, and results are clustered to identify distinct binding modes. The number of optimization steps adapts automatically based on problem complexity.

Exhaustiveness

The exhaustiveness parameter controls the thoroughness of the conformational search by setting the number of independent docking runs. Higher values increase the probability of finding the global energy minimum, reduce result variance between runs, and scale computational time linearly. The default value of 8 is suitable for rapid screening, while values of 16–32 are recommended for publication-quality results.

Flexible residue docking

Standard docking treats the protein as rigid, which can miss binding modes that require protein conformational changes (induced fit). Vina addresses this limitation by allowing selected side chains to move during docking.

When to use flexible docking

Flexible residue docking is appropriate when:

- The binding site contains residues known to undergo conformational changes

- Cross-docking (docking to a structure crystallized with a different ligand)

- The target protein has a known gatekeeper residue

- Initial rigid docking produces poor results

Adding flexible residues significantly increases computational cost. Limiting selection to 2–4 critical residues balances accuracy with tractability.

Limitations

Several constraints should be considered when using AutoDock Vina:

- Rigid protein backbone: Only side chains can be made flexible; backbone flexibility is not supported

- Scoring function accuracy: Empirical scoring functions have inherent limitations in predicting absolute binding affinities

- Metal coordination: Standard Vina poorly handles metalloproteins; use the AutoDock4 scoring function or alternative tools

- Large ligands: Accuracy decreases for ligands with many rotatable bonds (>10)

- Entropic effects: Water-mediated interactions and explicit solvation are not modeled

Related tools

Several docking tools derive from or complement AutoDock Vina:

- GNINA — Fork of Vina using deep learning (CNN) for scoring. Better accuracy but requires GPU for optimal performance. Handles metal-containing ligands.

- Smina — Fork with additional scoring functions including Vinardo. Useful for custom scoring function development.

- DiffDock — AI-based docking using diffusion models. Different approach that may perform better on challenging targets.

- AutoDock GPU — GPU-accelerated version of AutoDock 4 for high-throughput virtual screening.

In benchmark comparisons, GNINA achieves 73% Top-1 success rate versus Vina's 58% for redocking tasks, though Vina remains faster for high-throughput virtual screening.

Applications

AutoDock Vina is applied across drug discovery workflows:

- Virtual screening: Filtering large compound libraries (millions of molecules) to prioritize candidates for experimental testing

- Lead optimization: Evaluating how structural modifications affect binding to guide medicinal chemistry

- Binding mode prediction: Understanding how known drugs interact with their targets

- Selectivity profiling: Comparing binding across related proteins to predict off-target effects

- Structure-activity relationship (SAR): Rationalizing experimental activity data with predicted binding poses