Key takeaways

- Protein folding transforms a linear amino acid chain into a specific 3D structure that determines biological function.

- The "folding problem"—predicting structure from sequence—was solved by AlphaFold 2 in 2020, winning the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- Misfolded proteins cause diseases including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and prion disorders like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- AI tools like AlphaFold 2 and ESMFold now predict structures for entire proteomes with near-experimental accuracy.

What is protein folding?

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein, synthesized by a ribosome as a linear chain of amino acids, changes from an unstable random coil into an ordered three-dimensional structure. This structure, known as the "native state", permits the protein to become biologically functional.

The central principle is that all information required for a protein to adopt its correct 3D conformation is encoded in its amino acid sequence. This is known as Anfinsen's dogma, which was established in 1961 when Christian Anfinsen demonstrated that the enzyme ribonuclease A could spontaneously refold to its active form after being completely unfolded. His work earned the 1972 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The human genome encodes approximately 20,000 proteins, each requiring precise folding to function. A single misfolded protein can trigger cellular dysfunction and disease.

Why does protein folding matter?

A protein's function is entirely determined by its shape. Enzymes catalyze reactions because their active sites are precisely shaped to bind substrates. Antibodies recognize pathogens because their variable regions fold into specific 3D configurations. Structural proteins like collagen and keratin derive their mechanical properties from their folded architectures.

Misfolded proteins aggregate into toxic deposits linked to Alzheimer's disease (beta-amyloid plaques), Parkinson's disease (alpha-synuclein aggregates), and prion diseases (misfolded PrP protein). Understanding how proteins fold and why they sometimes misfold is fundamental to treating these conditions.

For drug discovery, knowing a protein's structure reveals its binding pockets and interaction surfaces. This enables rational drug design through molecular docking, where researchers computationally screen compounds that fit a target's 3D shape.

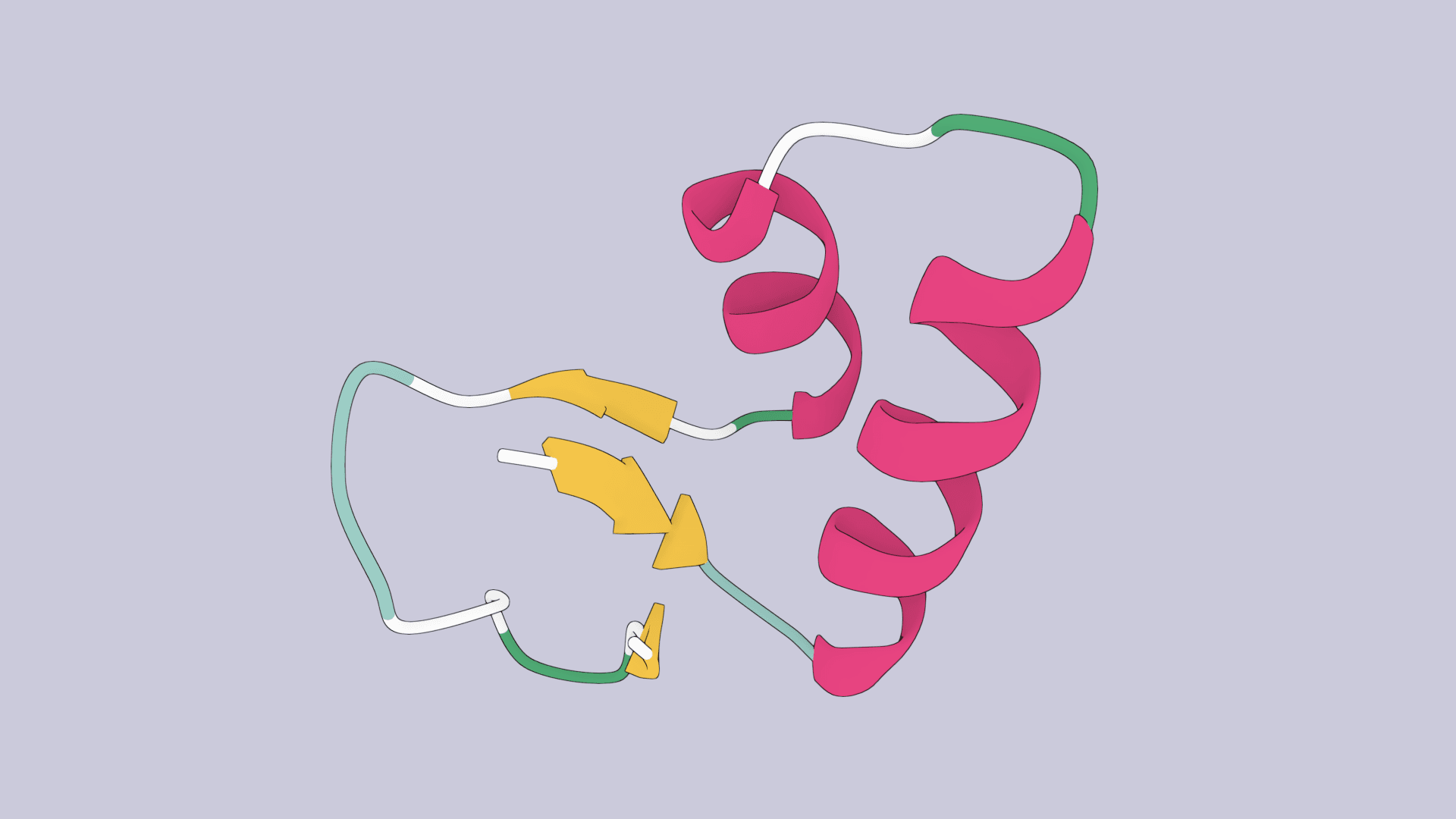

How does protein folding work?

Proteins don't sample random conformations until they stumble upon the right one. Instead, they follow an "energy landscape" shaped like a funnel. At the top, the unfolded chain has high energy and many possible conformations. As the protein forms local structures, such as secondary structure elements and hydrophobic cores, it moves downward toward lower energy states. The native state sits at the funnel's bottom: the minimum free energy conformation.

This "folding funnel" model, developed by José Onuchic and Peter Wolynes, explains how proteins reliably reach their native state through many different pathways rather than a single obligatory route.

Several molecular interactions drive the folding process:

- Hydrophobic effect: Nonpolar amino acid side chains cluster in the protein's interior to minimize contact with water. This is the dominant driving force for folding.

- Hydrogen bonds: Form between backbone atoms (creating secondary structures like alpha helices and beta sheets) and between side chains.

- Ionic interactions: Electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged amino acids (e.g., lysine and glutamate) stabilizes the folded structure.

- Disulfide bridges: Covalent bonds between cysteine residues lock regions of the protein together.

- Van der Waals forces: Weak attractions between closely packed atoms contribute to overall stability.

However, not all proteins fold spontaneously in the cell. Specialized helper proteins called molecular chaperones assist folding by:

- Preventing premature aggregation of newly synthesized chains

- Providing protected environments (like the GroEL/GroES barrel) where proteins can fold without interference

- Rescuing misfolded proteins and giving them another chance to fold correctly

Chaperones don't add information about how to fold. They simply prevent errors by keeping unfolded proteins from sticking together before they've finished folding.

Is there a solution to protein folding?

The "protein folding problem" asks: given an amino acid sequence, can we predict the protein's 3D structure? This question has occupied researchers for over 50 years.

Levinthal's paradox

In 1969, Cyrus Levinthal calculated that if a protein had to randomly sample every possible conformation, it would take longer than the age of the universe to find the right one. A 100-residue protein has roughly 10^300 possible conformations. Yet real proteins fold in milliseconds to seconds.

The resolution: proteins don't search randomly. Local structure forms first (helices, turns), which constrains global options. The energy landscape guides the chain downhill toward the native state. Evolution has selected sequences that fold reliably and quickly.

Traditional experimental methods

Before computational prediction, determining a protein's structure required experimental techniques:

| Method | Resolution | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray crystallography | < 2 Å | Requires crystals; captures only one conformation |

| Cryo-electron microscopy | 2-4 Å | Best for large complexes; lower resolution than X-ray |

| NMR spectroscopy | Atomic | Limited to small proteins (< 40 kDa) |

These methods are slow and expensive. Crystallizing a single protein can take months. As of 2024, only about 220,000 experimental protein structures exist in the RCSB Protein Data Bank—a tiny fraction of the hundreds of millions of known protein sequences.

AlphaFold

In December 2020, DeepMind's AlphaFold 2 achieved a median Global Distance Test (GDT) score of 92.4 at CASP14. This performance matched experimental accuracy for most targets, effectively "solving" the structure prediction problem.

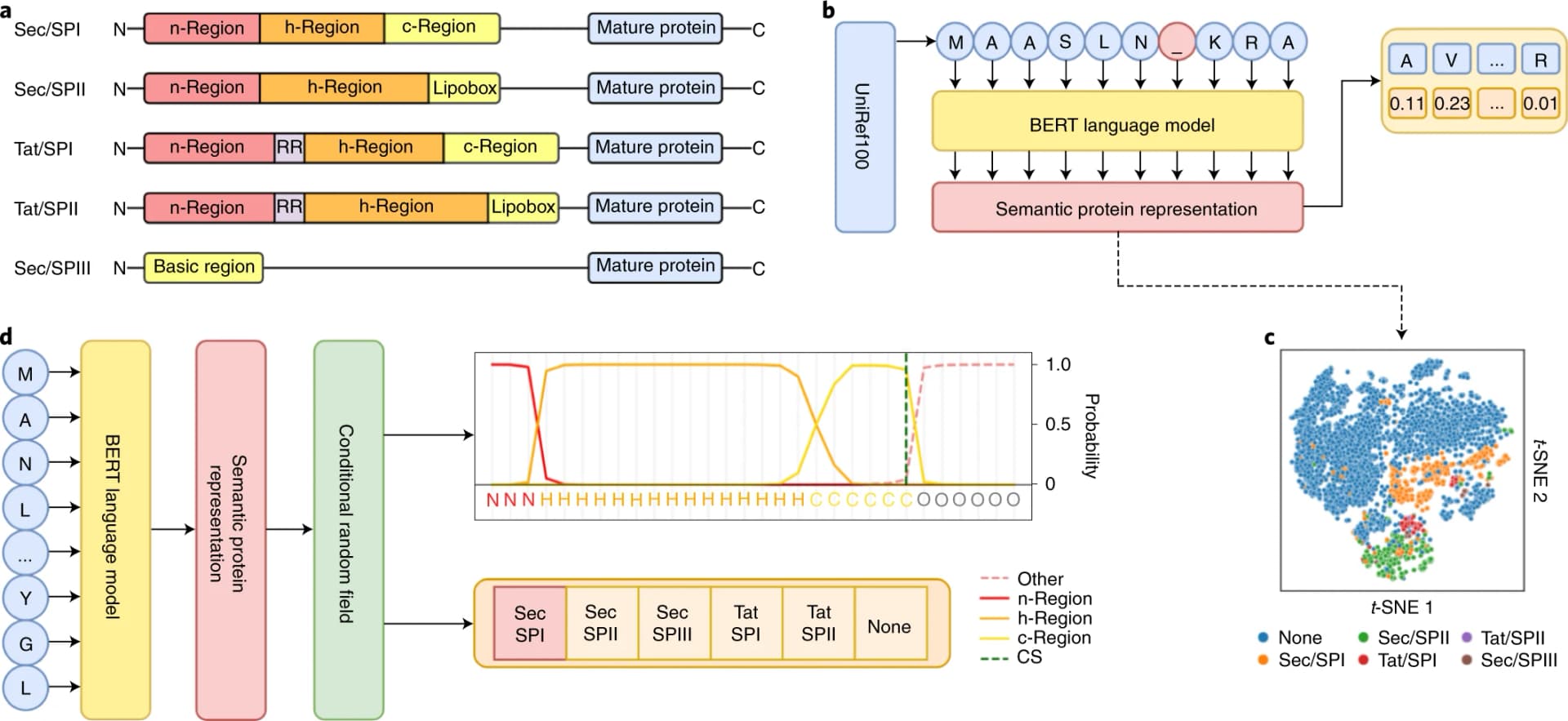

AlphaFold 2 works by:

- Searching sequence databases for evolutionarily related proteins (multiple sequence alignment)

- Using a neural network architecture called "Evoformer" to reason about pairwise relationships between residues

- Iteratively refining atomic coordinates until convergence

The AlphaFold Protein Structure Database now contains predicted structures for over 214 million proteins—covering nearly every known protein sequence.

Demis Hassabis and John Jumper of DeepMind shared the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold 2. The prize recognized that "computational protein design and protein structure prediction" had reached a level where computational methods match experimental approaches.

Announced in May 2024, AlphaFold 3 extends beyond single proteins to predict structures of complexes involving proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, and ions. It uses a diffusion-based architecture (instead of the iterative refinement of AlphaFold 2) to generate molecular structures.

Open-source alternatives

Several tools provide similar capabilities with more permissive licenses:

- ESMFold — Meta AI's language-model-based predictor; faster than AlphaFold 2 for single sequences

- OpenFold 3 — Open-source implementation of AlphaFold 3 (MIT license)

- Boltz-2 — Open-source AlphaFold 3 clone (MIT license)

- Protenix — ByteDance's open-source implementation (Apache 2.0)

- CHAI-1 — Predicts protein complexes and protein-ligand structures

- RoseTTAFold 3 — David Baker's lab alternative with full open-source access

Applications of protein structure prediction

Drug discovery

Knowing a target's structure accelerates every stage of drug development, from identifying druggable pockets on disease-related proteins to docking millions of compounds against predicted structures using tools like AutoDock Vina or DiffDock. New protein folding algorithms can also help visualize binding interactions to guide medicinal chemistry.

Protein engineering

Predicted structures guide the design of proteins with novel functions:

- ProteinMPNN — Designs sequences that fold into target structures

- RFDiffusion — Generates novel protein backbones from scratch

- BindCraft — Designs proteins that bind specified targets

These tools enable de novo protein design—creating proteins that never existed in nature but fold stably and perform designed functions.

Understanding disease mechanisms

Predicted structures reveal how mutations cause disease:

- Map disease-associated variants onto 3D structures to identify affected regions

- Predict whether a mutation will destabilize the folded state

- Model how misfolded intermediates might aggregate

Limitations of structure prediction

Despite remarkable progress, computational structure prediction has important limitations:

Dynamics and flexibility

Predicted structures represent a single static conformation. Real proteins are dynamic—they breathe, flex, and undergo conformational changes essential to function. For understanding mechanism, molecular dynamics simulations remain necessary.

Confidence varies by region

AlphaFold 2 provides per-residue confidence scores (pLDDT). Some regions—particularly intrinsically disordered regions—have genuinely no fixed structure, and low confidence correctly reflects biological reality rather than prediction failure.

Complexes and interactions

While AlphaFold 3 predicts multi-chain complexes, accuracy for protein-protein interfaces and protein-ligand binding remains lower than for single-chain structure. Experimental validation is still essential for understanding specific interactions.

Not a replacement for experiment

Computational predictions are hypotheses. Critical applications (drug design, mechanistic studies) require experimental validation through crystallography, cryo-EM, or biochemical assays.

The bottom line

Protein folding—the process by which amino acid chains transform into functional 3D structures—is fundamental to understanding how life works at the molecular level. The computational solution to the protein folding problem, achieved by AlphaFold 2, represents one of the most significant scientific breakthroughs of the 21st century. Researchers now have instant access to structural information that previously required years of experimental work.

Yet structure prediction is a tool, not an endpoint. The real value lies in what researchers do with predicted structures: designing new drugs, engineering novel proteins, and understanding the molecular basis of disease.

Try protein folding tools on ProteinIQ

Ready to predict protein structures or analyze folding? ProteinIQ offers code-free access to state-of-the-art tools:

Structure prediction:

- AlphaFold 2 — The gold standard for single-chain structure prediction

- ESMFold — Fast, language-model-based prediction

- OpenFold 3 — Open-source implementation of AlphaFold 3

- Boltz-2 — Open-source AlphaFold 3 alternative

- CHAI-1 — Protein complex and protein-ligand structure prediction

- RoseTTAFold 3 — Baker lab's open-source predictor

Structure validation:

- MolProbity — Comprehensive structure quality assessment

- Ramachandran Plot — Validate backbone geometry

- DSSP — Secondary structure assignment

Conformational dynamics:

Protein design:

- ProteinMPNN — Design sequences for target structures

- RFDiffusion — Generate novel protein backbones

- BindCraft — Design proteins that bind specified targets

No installation required. Upload your sequence and start predicting structures in minutes.

FAQs

How long does it take for a protein to fold?

Small proteins fold in microseconds to milliseconds. Larger proteins may take seconds to minutes. The fastest known folders (like villin headpiece) complete folding in about 5 microseconds. Proteins assisted by chaperones may take longer due to the iterative nature of chaperone-assisted folding.

Can you predict protein structure from sequence alone?

Yes. Tools like AlphaFold 2 and ESMFold predict 3D structures from amino acid sequences with near-experimental accuracy for most proteins. AlphaFold 2 achieves median accuracy comparable to X-ray crystallography for well-folded domains.

What causes proteins to misfold?

Misfolding can result from:

- Genetic mutations that destabilize the native fold

- Environmental stress (heat, pH changes, oxidative damage)

- Aging-related decline in chaperone function

- Overexpression that overwhelms cellular folding machinery

What is the difference between protein folding and protein structure prediction?

Protein folding is the physical process occurring in cells. Protein structure prediction is the computational problem of determining a protein's 3D shape from its sequence. AlphaFold 2 solves structure prediction without simulating the folding process—it directly predicts the final structure.

How accurate is AlphaFold 2?

AlphaFold 2 achieves a median GDT score of 92.4 on CASP14 blind prediction targets, comparable to experimental methods. However, accuracy varies: well-structured domains are highly accurate, while intrinsically disordered regions and multi-chain interfaces have lower reliability.

Can misfolded proteins be fixed?

Cells have quality control systems to refold or degrade misfolded proteins. Molecular chaperones attempt to refold proteins. If refolding fails, the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy pathways degrade them. These systems become less efficient with age, contributing to protein misfolding diseases.

References

ProteinIQ uses primary sources to support our content, including peer-reviewed research, official tool documentation, and original reporting.

-

Anfinsen, C.B. (1973). Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science, 181(4096), 223-230. DOI

-

Levinthal, C. (1969). How to Fold Graciously. Mössbauer Spectroscopy in Biological Systems, 67, 22-24.

-

Bryngelson, J.D., Onuchic, J.N., Socci, N.D., Wolynes, P.G. (1995). Funnels, pathways, and the energy landscape of protein folding: A synthesis. Proteins, 21(3), 167-195. DOI

-

Jumper, J., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596, 583-589. DOI

-

Lin, Z., et al. (2023). Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science, 379(6637), 1123-1130. DOI

-

Varadi, M., et al. (2024). AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Research, 52(D1), D368-D375. DOI

-

Hartl, F.U., Bracher, A., Hayer-Hartl, M. (2011). Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature, 475, 324-332. DOI

-

Knowles, T.P., Vendruscolo, M., Dobson, C.M. (2014). The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 15, 384-396. DOI

-

Prusiner, S.B. (1998). Prions. PNAS, 95(23), 13363-13383. DOI

-

Dobson, C.M. (2003). Protein folding and misfolding. Nature, 426, 884-890. DOI