Key takeaways

- Molecular docking predicts both where a ligand binds and how strongly it binds to a protein target.

- Two core components work together: search algorithms explore binding poses; scoring functions estimate affinity.

- Modern AI tools (DiffDock, GNINA) improve pose prediction, but affinity scoring remains the field's biggest challenge.

- Garbage in, garbage out—proper receptor and ligand preparation determines result quality.

What is molecular docking?

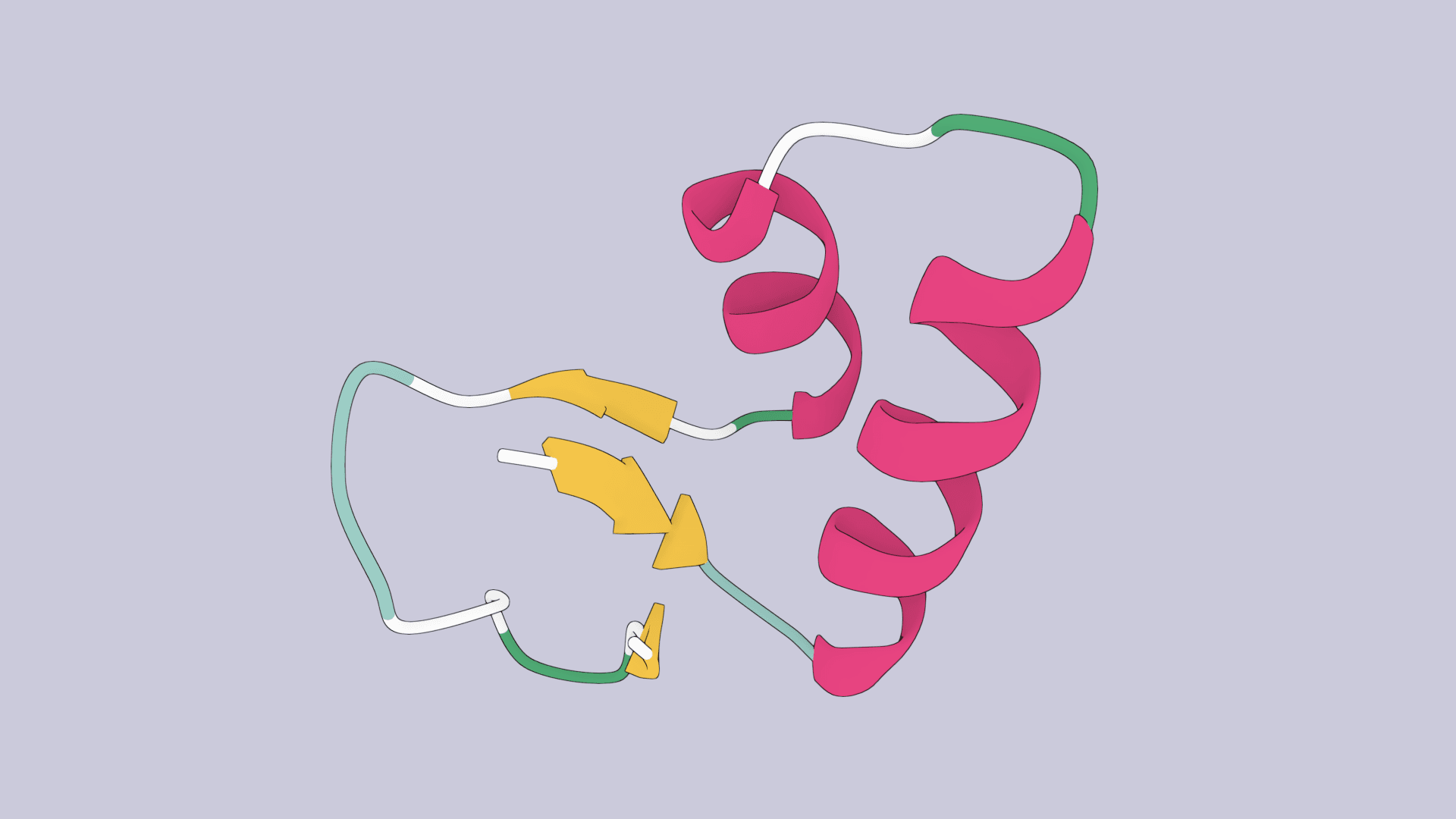

Molecular docking is a computational technique used to predict how two molecules—usually a small molecule "ligand" and a protein "receptor"—bind together. The goal is to find the orientation that fits best and forms the most stable complex.

A docking experiment typically answers two questions:

- Pose prediction: What does the ligand look like in the binding site? (Which way is it facing? Which atoms are interacting?)

- Affinity prediction: How strong is the interaction? (Will it bind at nanomolar concentrations or millimolar?)

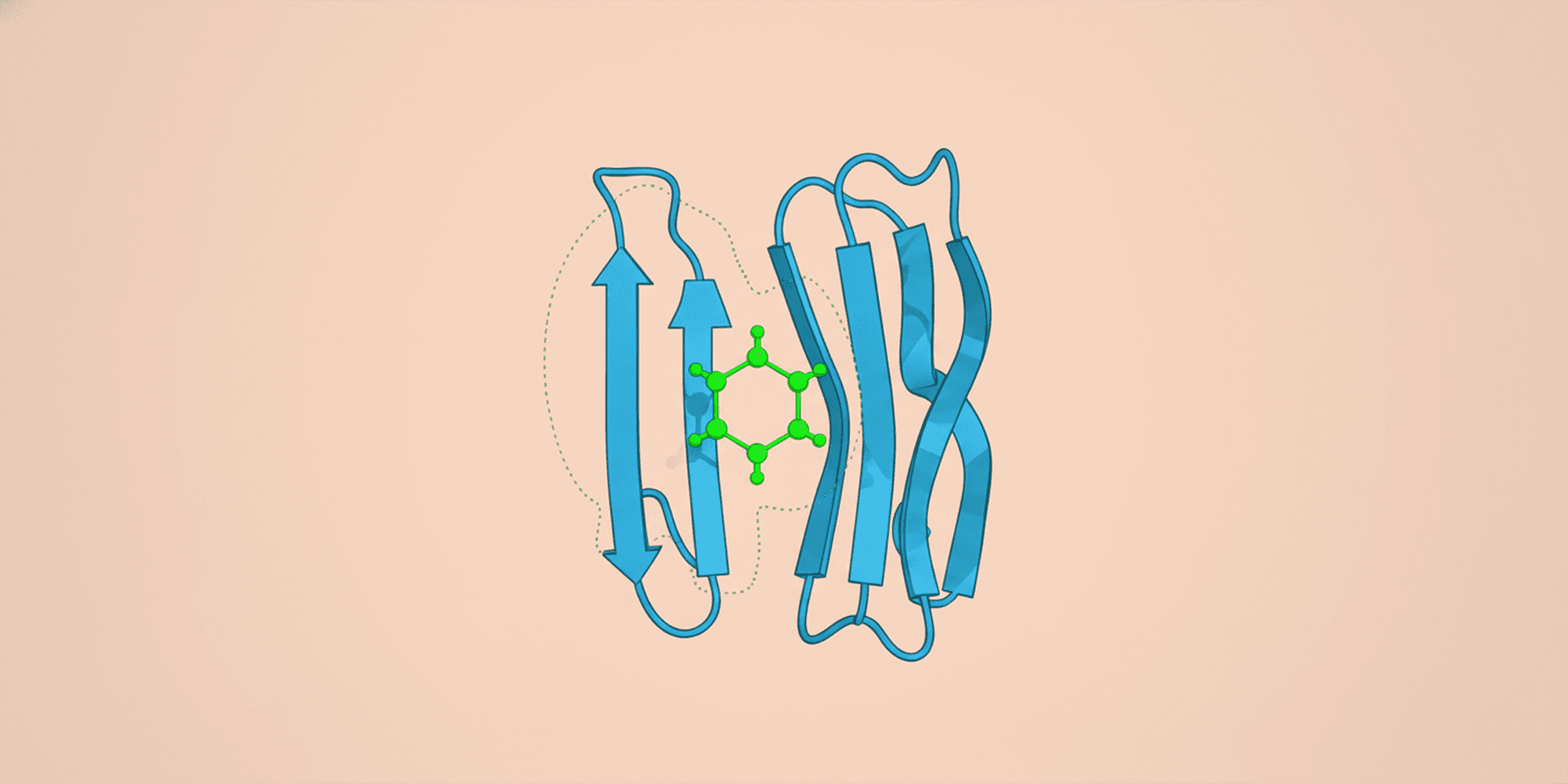

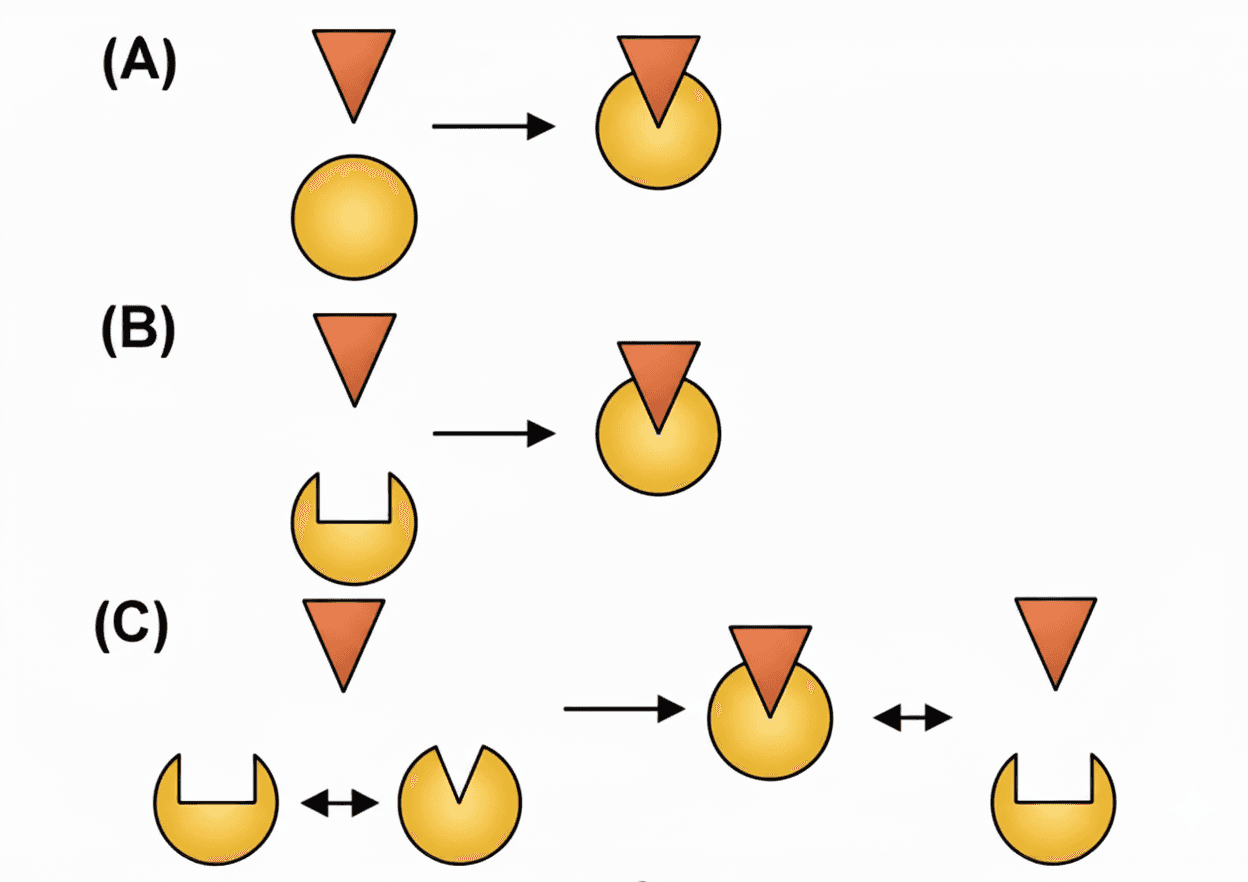

The classic "lock-and-key" model assumes the ligand fits perfectly into a static receptor. However, proteins are flexible, and binding often follows an "induced-fit" model where both molecules shift shape to accommodate each other.

How does molecular docking work?

Docking software is not a single algorithm but a coupling of two independent mathematical components: the search algorithm (the sampler) and the scoring function (the evaluator).

The search algorithm (sampling)

The search space in protein-ligand docking is high-dimensional and rugged. A typical drug-like molecule has 3 to 15 rotatable bonds, plus six degrees of translational and rotational freedom relative to the protein.

The algorithm must explore this large energy landscape to locate the global minimum. To do this, there are a few methods:

- Systematic search: Explores conformations by incrementally rotating bonds. While exhaustive, this approach faces "combinatorial explosion" and is computationally intractable for ligands with many rotatable bonds.

- Stochastic (random) search: The industry standard. Algorithms like Monte Carlo (MC) or Genetic Algorithms (GA) (used in AutoDock and GOLD) apply random changes to the ligand's coordinates. If a change improves the score, it is accepted; if not, it is probabilistically rejected (Metropolis criterion). This mimics natural selection to evolve towards a global minimum.

- Generative diffusion: A new paradigm (e.g., DiffDock) that treats docking not as an energy optimization problem but as a generative modeling task, "denoising" random atomic coordinates into a chemically plausible binding pose.

The scoring function (evaluation)

Once the algorithm places a ligand, the scoring function evaluates the "fitness" of that pose. Because calculating the true free energy of binding using rigorous free energy perturbation (FEP) is too slow for screening millions of compounds, docking uses simplified approximations.

- Force-field based: Estimates enthalpy using standard molecular mechanics terms: Lennard-Jones potentials for Van der Waals forces and Coulombic terms for electrostatics.

- Empirical: Uses a weighted sum of chemically intuitive terms (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, rotatable bond penalties) calibrated against a training set of experimental crystal structures with known binding affinities ( or ).

- Knowledge-based (statistical): Derives potentials from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) statistics. If a specific atomic contact (e.g., carbonyl oxygen 2.8Å from an amide nitrogen) occurs frequently in nature, it is assigned a favorable score (inverse Boltzmann).

- ML-based: Uses neural networks (e.g., 3D-CNNs in GNINA) to classify poses based on voxelized representations of the protein-ligand interface, often outperforming classical physics-based functions in ranking.

Types of molecular docking

Docking protocols are categorized by how they handle system flexibility and the definition of the binding site.

Flexible ligand docking

Most standard docking runs keep the protein rigid and only let the ligand move. This is the industry standard for virtual screening because it's fast. Tools like AutoDock Vina, Glide, and GOLD primarily operate this way. It works well if your crystal structure is already in a conformation that fits the ligand (e.g., re-docking or docking similar analogs).

Flexible receptor docking

Sometimes the protein must move to accommodate a ligand. "Soft docking" allows limited flexibility by softening the repulsive forces, letting atoms overlap slightly. More rigorous methods like Induced Fit Docking (IFD) explicitly model side-chain movements. This is critical when targeting a closed pocket that only opens upon binding, but it significantly increases search space complexity.

Ensemble docking

Instead of trying to make one protein structure flexible, you can dock against multiple static structures of the same protein (an "ensemble"). These might come from different crystal structures or snapshots from an MD simulation. This is often the most practical way to handle protein flexibility in large screens—if a ligand fits any of the dominant conformations, it's considered a hit.

Covalent docking

Some drugs don't just bind—they react. Covalent inhibitors form a chemical bond with a specific residue (often cysteine or serine) in the binding site. Specialized protocols in tools like CovDock or GNINA model both the non-covalent approach and the final bond formation.

Artificial intelligence

Deep learning is changing the field rapidly. DiffDock treats docking as a generative diffusion problem rather than a search-and-score problem, often finding correct poses much faster than classical methods. GNINA uses 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to score poses with high accuracy.

How to start molecular docking?

A molecular docking campaign involves three distinct phases: preparation, simulation, and analysis. The reliability of the output is strictly determined by the physicochemical accuracy of the input ("garbage in, garbage out").

1. Structure preparation

Raw PDB files are rarely suitable for direct simulation. X-ray crystallography often fails to resolve hydrogen atoms, leading to ambiguous valencies.

First steps include adding hydrogens, optimizing hydrogen bonding networks (flipping Asn/Gln/His residues), and removing non-essential bulk water. However, you should preserve structural waters that bridge ligand-protein interactions. A great tool for this is PDBFixer by OpenMM.

If you have 2D inputs, like SMILES, you must expand them to 3D. Crucially, the protonation state and tautomeric forms must be generated at physiological pH (7.4). An incorrect charge assignment on a critical residue (e.g., a protonated vs. deprotonated imidazole) will invalidate the electrostatic scoring terms.

2. Running the simulation

The prepared coordinates are fed into the docking engine. For High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS), speed is prioritized (seconds per ligand). For lead optimization, precision settings (exhaustiveness or number of Monte Carlo steps) are increased to ensure thorough sampling of the energy landscape.

3. Post-docking analysis

The output is a ranked list of poses. Researchers analyze these visually and statistically.

- Visual inspection: The most reliable filter. Researchers check for unsatisfied hydrogen bond donors, buried hydrophobic groups, and strain in the ligand's conformation.

- RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation): Used primarily during protocol validation (re-docking) to measure how close the predicted pose is to the experimental crystal structure. A successful dock typically has an RMSD < 2.0 Å.

What is molecular docking used for?

While molecular docking is most famous for finding new drugs, its utility spans the entire discovery pipeline, from the initial search for active compounds to figuring out why a drug causes specific side effects. It serves as a bridge between chemical theory and biological reality.

High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS)

This is the "funnel" approach and the most common application of docking. In a physical laboratory, synthesizing and testing 100,000 compounds is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. In a computational environment, however, docking allows researchers to screen millions of commercially available compounds against a protein target in a matter of days.

The primary goal here is not necessarily to find the perfect drug immediately, but to improve the "enrichment factor." By filtering out molecules that physically cannot fit the binding site, docking narrows the field down to a manageable list—perhaps the top 1%—which has a much higher probability of containing active "hits" than a random selection.

Lead optimization

Once a promising molecule (a "hit") is identified, it is rarely potent enough to be a drug. It might bind in the micromolar range, whereas a clinical drug usually needs to act in the nanomolar range. Docking facilitates "rational design" during this phase to bridge this gap.

By visualizing the docked pose of the hit, medicinal chemists can see exactly where the molecule fits well and where it fits poorly. They might identify a small gap between the ligand and a hydrophobic pocket in the protein, suggesting that adding a methyl group to that specific position would fill the void. This structural insight guides the synthesis of new analogs, turning a weak hit into a potent lead candidate.

Target identification and reverse docking

While standard docking fits many ligands into one receptor, "reverse docking" fits one ligand into many different receptors. This is particularly useful for identifying off-target effects. If a drug candidate shows unexpected toxicity in animal trials, researchers can dock that specific molecule against a panel of common human proteins to identify unintended interactions that could explain the side effects.

Conversely, this method is used to breathe new life into old drugs. By docking an FDA-approved drug against a library of disease targets, scientists can discover if an existing medication interacts with a target relevant to a completely different disease, a process known as drug repurposing.

Elucidating mechanisms of action

Sometimes experimental data confirms that a molecule inhibits a protein, but techniques like X-ray crystallography or Cryo-EM fail to capture the structure of the complex. This often happens because the protein-ligand complex is unstable, transient, or simply difficult to crystallize.

Docking provides a structural hypothesis in these scenarios. It generates a predictive 3D model of the interaction, helping scientists understand the specific mechanism of inhibition, such as whether the drug blocks the active site directly or induces a shape change from a distance. These models are often used to design "mutational validation" experiments to confirm the predicted binding mode in the lab.

What are the limitations of molecular docking?

Docking is a simulation based on specific physical approximations. It serves as a model to prioritize hypotheses, not as a replacement for thermodynamic measurements.

The scoring problem

Molecular docking algorithms struggle the most to accurately predict binding affinity. While search algorithms are generally successful at finding the correct pose (geometry), scoring functions struggle to rank these poses by energy.

Standard scoring functions are additive and often fail to capture complex thermodynamic phenomena such as cooperativity and polarization. Consequently, docking scores often correlate poorly with experimental

IC50IC_{50}IC50

data. A "high score" (very negative energy) indicates good geometric fit, but does not guarantee a strong binder in vitro.

The rigid receptor assumption

To maintain computational speed, most docking protocols treat the protein as a rigid body. In reality, proteins are dynamic ensembles. If a binding pocket exists in a "closed" conformation in the input PDB structure, rigid docking will fail to identify binders that require the pocket to open ("induced fit"). While ensemble docking (using multiple protein conformations) mitigates this, it increases the computational burden.

Entropic approximations

Binding is a balance between enthalpy (favorable interactions) and entropy (unfavorable loss of disorder). When a flexible ligand binds, it loses rotational and translational degrees of freedom—a massive energetic penalty known as the entropic cost of binding.

Docking scoring functions often rely on crude approximations, such as counting rotatable bonds, to estimate this penalty. This frequently leads to the over-scoring of large, flexible molecules that can form many contacts but would be entropically disfavored in reality.

Solvation and desolvation

Water plays an important role in binding. The displacement of high-energy water molecules from a hydrophobic pocket is often the primary driver of binding affinity. However, most docking tools utilize implicit solvent models, treating water as a continuum rather than explicit molecules. This simplification can lead to false negatives (missing water-mediated bridges) or false positives (underestimating desolvation penalties).

The bottom line

Molecular docking is an imperfect but essential tool in computational drug discovery. It excels at narrowing millions of compounds down to a testable set of candidates. The keys to success: invest time in structure preparation, don't over-trust individual scores, and always validate against experimental data when possible.

With AI-powered tools like DiffDock improving accuracy and platforms like ProteinIQ making these methods accessible, docking is becoming a practical starting point for any drug discovery project.

Try molecular docking on ProteinIQ

Ready to run your own docking simulations? ProteinIQ offers code-free access to industry-standard docking tools:

- AutoDock Vina — The most popular open-source docking program

- GNINA — ML-enhanced docking with CNN scoring

- DiffDock — State-of-the-art diffusion-based docking

- Smina — AutoDock Vina fork optimized for high-throughput screening

- AutoDock-GPU — GPU-accelerated docking for large-scale campaigns

No installation required. Upload your structures and start docking in minutes.

FAQs

What is the difference between molecular docking and molecular dynamics?

Molecular docking is a static snapshot—it predicts how a ligand might bind at a single moment. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulates atomic movements over time, capturing flexibility and conformational changes. Docking is faster and used for screening; MD is slower but provides realistic binding pathway information.

How accurate is molecular docking?

Pose prediction (finding the correct binding geometry) achieves ~70-80% success for poses within 2Å RMSD of experimental structures. Affinity prediction (ranking binding strength) is less reliable—docking scores correlate weakly with experimental binding affinities.

Which docking software should I use?

It depends on your goal:

- AutoDock Vina: Fast, reliable, best for large virtual screens

- DiffDock: AI-powered, better pose accuracy for difficult targets

- GNINA: CNN-based scoring, good for rescoring and ML applications

- AutoDock-GPU: GPU-accelerated throughput for large campaigns

Can molecular docking replace experimental testing?

No. Docking is a computational filter that prioritizes compounds for experimental validation. It cannot replace binding assays, crystallography, or functional studies.

References

ProteinIQ uses primary sources to support our content, including peer-reviewed research, official tool documentation, and original reporting.

- Fischer, E. (1894). Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 27(3), 2985-2993. DOI

- Koshland, D.E. (1958). Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis. PNAS, 44(2), 98-104. PMC

- Trott, O., Olson, A.J. (2010). AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 31(2), 455-461. DOI

- Corso, G. et al. (2023). DiffDock: Diffusion Steps, Twists, and Turns for Molecular Docking. ICLR. arXiv

- McNutt, A.T. et al. (2021). GNINA 1.0: molecular docking with deep learning. Journal of Cheminformatics, 13, 43. DOI