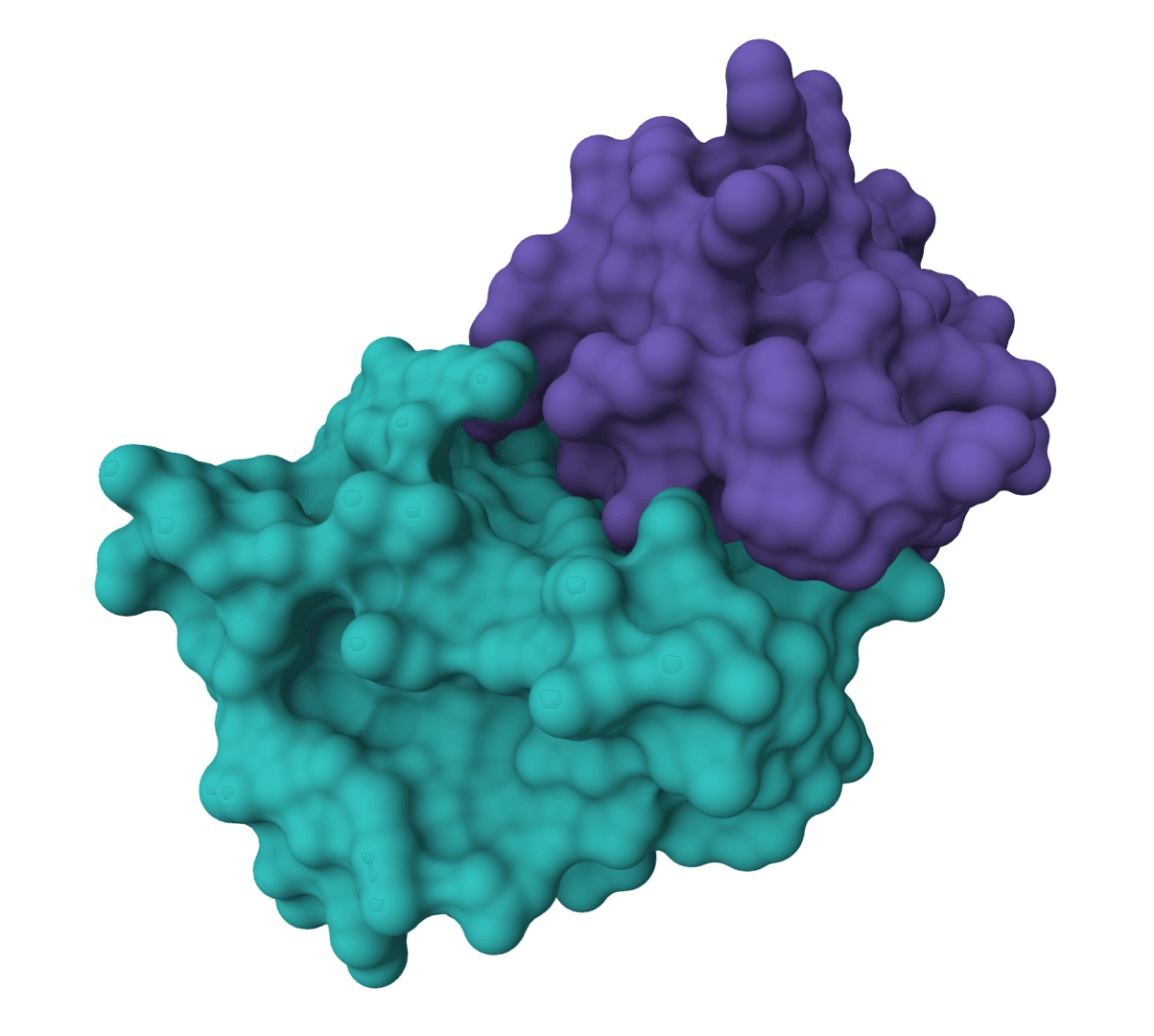

What is ColabDock?

ColabDock is a protein-protein docking framework that integrates AlphaFold2 with experimental restraints to predict how proteins bind to each other. Developed by Feng and colleagues at Peking University, it was published in Nature Machine Intelligence in August 2024.

Unlike traditional docking methods that use Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithms like ZDOCK, HADDOCK, or ClusPro, ColabDock uses gradient backpropagation to optimize docking poses. This approach automatically integrates the AlphaFold2 energy function with experimental data without requiring retraining.

ColabDock is particularly useful when you have experimental data about protein-protein interfaces—such as cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS), NMR chemical shift perturbation, or covalent labeling experiments. The method outperforms HADDOCK and ClusPro on benchmarks using both simulated and real experimental restraints.

How does ColabDock work?

Generation stage

ColabDock operates in two stages. The generation stage uses ColabDesign, a protein design framework built on AlphaFold2, to create initial complex structures.

During generation, the model optimizes sequence representations in logit space while minimizing four loss functions: a monomer distogram loss (preserving individual chain conformations), a restraint loss (bringing specified residues close together), and pLDDT/ipAE losses (ensuring high-quality predictions). The weighted combination of these losses guides the model toward structures that satisfy both the input templates and experimental constraints.

Prediction stage

After generation, AlphaFold2 predicts the final complex structure using the generated conformation as a guide. This two-stage approach combines the flexibility of gradient-based optimization with AlphaFold2's accuracy.

Ranking algorithm

ColabDock ranks output structures using a RankingSVM model trained on five features: ipTM (interface quality), contact number, contact pLDDT, number of satisfied restraints, and average error. This ranking helps identify the most likely binding mode when multiple conformations are generated.

Input requirements

Protein inputs

ColabDock requires 2-4 protein structures as input. You can upload PDB files directly or fetch structures from the RCSB database using their PDB IDs.

The proteins you provide are docked together to form a complex. For typical binary complexes, provide the two interacting proteins. For larger assemblies, you can include up to four chains.

Reference complex (optional)

If you have a known complex structure—even from homologous proteins—you can use it to automatically extract restraints. ColabDock samples interface contacts from the reference and uses them to guide docking.

This is useful when you have a related complex structure but want to dock different proteins, or when benchmarking against a known answer.

Restraint types

Experimental restraints encode spatial relationships between residues—typically from cross-linking, NMR, or mutagenesis experiments. ColabDock supports four restraint formats with increasing flexibility.

1v1 restraints (specific pairs)

The simplest restraint type: two specific residues should be in contact. Format each restraint as chain:residue,chain:residue on separate lines.

Example: A:4,B:15 means residue 4 of chain A should contact residue 15 of chain B.

Use 1v1 restraints when you have precise residue-level data, such as identified cross-linked peptide pairs.

1vN restraints (one to range)

When you know one residue contacts somewhere within a region—but not the exact partner—use 1vN restraints. Format: chain:residue,chain:start-end.

Example: A:4,B:13-18 means residue 4 of chain A contacts at least one residue between 13-18 of chain B.

This accommodates experimental uncertainty or lower-resolution data like NMR chemical shift perturbation that identifies affected regions rather than specific residues.

MvN restraints (multiple with minimum)

For ambiguous data where several restraints could be satisfied, MvN allows you to specify that only some must be true. Format: pair1;pair2;...|min_count.

Example: A:4,B:13-18;A:6,B:13-18|1 means at least one of the two constraints must be satisfied.

This is valuable for noisy experimental data where some cross-links may be false positives.

Repulsive restraints (keep apart)

Some experiments reveal which regions do NOT interact. Repulsive restraints force specified residue pairs to remain distant. Format: chain:residue,chain:residue.

Example: A:6,B:18 means residue 6 of chain A should be far from residue 18 of chain B.

Use repulsive restraints when you have negative data—regions that definitively don't form the interface.

Prediction parameters

- Number of samples: How many docked conformations to generate. More samples provide conformational diversity but increase runtime.

- Optimization rounds: Number of generation-prediction cycles. Additional rounds can improve results for difficult cases.

- Steps per round: Backpropagation steps during optimization. Most cases converge within 50 steps; increase for challenging targets.

Reference extraction options

When using a reference complex, these settings control how restraints are automatically extracted:

- Receptor chains: Chain IDs in the reference that represent the receptor (the protein held fixed during extraction).

- Ligand chains: Chain IDs representing the mobile partner. Restraints are sampled from contacts between receptor and ligand chains.

- Restraint type: Format of extracted restraints—

1v1,1vN, orMvN. - Number of restraints: How many restraints to randomly sample from the interface.

Advanced options

- Contact threshold: Distance cutoff for defining contacts in Angstroms. The

8.0Å default is standard for cross-linking studies. Increase for longer cross-linkers. - Repulsive threshold: Minimum distance for repulsive restraints. Residues should be farther apart than this value.

- Use AF2-Multimer: Enables the AlphaFold2-Multimer model, which is optimized for multi-chain prediction. We recommend keeping this enabled for most cases.

Understanding the results

ColabDock returns multiple ranked docking poses as PDB files. Lower rank numbers indicate better predicted complexes according to the RankingSVM scoring.

Examine the top 3-5 poses rather than relying solely on rank 1. Multiple similar top poses suggest a confident prediction, while diverse poses may indicate conformational flexibility or an uncertain binding mode.

If you provided restraints, check how many are satisfied in each pose. A good prediction should satisfy most attractive restraints while avoiding contacts flagged as repulsive.

Comparison to other docking tools

| Tool | Approach | Restraint support | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| ColabDock | AF2 + gradient backpropagation | 1v1, 1vN, MvN, repulsive | Data-driven docking with XL-MS/NMR |

| LightDock | Glowworm Swarm Optimization | Limited | Blind docking, flexibility |

| HADDOCK | FFT + refinement | Ambiguous restraints | NMR-driven docking |

| ClusPro | FFT + clustering | None | Blind docking screening |

ColabDock is the preferred choice when you have experimental restraint data. For blind docking without prior knowledge, consider LightDock or ClusPro.

Limitations

ColabDock has a maximum restraint distance of 22 Å, determined by AlphaFold2's distance map upper limit. This restricts compatibility to shorter cross-linking reagents; longer-range XL-MS data cannot be directly incorporated.

The method can process complexes up to approximately 1,200 residues on an NVIDIA A100 GPU. Larger assemblies require segment-based optimization or splitting into subcomplexes.

Without experimental restraints, ColabDock may not outperform dedicated blind docking tools. The method's strength lies in integrating experimental data with deep learning predictions.