What is MAFFT?

MAFFT (Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform) is a multiple sequence alignment program that aligns protein or nucleotide sequences to identify conserved regions and evolutionary relationships. It offers a range of algorithms that trade off between speed and accuracy, from ultra-fast progressive methods for thousands of sequences to highly accurate iterative methods for smaller datasets.

MAFFT's distinctive feature is its use of Fast Fourier Transform to rapidly identify homologous regions between sequences, dramatically reducing computation time compared to traditional dynamic programming approaches. For alternative alignment approaches, see Clustal Omega which uses HMM-based profile alignment.

How does MAFFT work?

MAFFT converts amino acid sequences into numerical representations based on volume and polarity, then uses FFT to rapidly compute correlations between sequences. This identifies conserved regions that serve as anchors, restricting the search space for subsequent dynamic programming alignment.

FFT-based homology detection

Traditional sequence comparison requires operations for two sequences of length using dynamic programming. MAFFT reduces this by converting sequences to waves based on physicochemical properties:

Each residue is represented as a 2D vector of volume and polarity values. The correlation between two sequence waves can be computed in time using FFT. Peaks in the correlation identify conserved regions that become anchors for alignment.

Progressive vs. iterative methods

MAFFT offers two fundamental strategies:

Progressive methods (FFT-NS-1, FFT-NS-2) build a guide tree from pairwise distances and align sequences following the tree order. FFT-NS-2 improves on FFT-NS-1 by rebuilding the guide tree from the initial alignment before a second pass.

Iterative refinement methods (L-INS-i, G-INS-i, E-INS-i) start with a progressive alignment, then repeatedly refine it. Each iteration divides the alignment into two groups and realigns them, continuing until the score stops improving.

Consistency-based scoring

The iterative methods incorporate consistency scores derived from all pairwise alignments. If residues A-B are aligned in sequence pair 1-2, and B-C are aligned in pair 2-3, consistency suggests A-C should align in pair 1-3. This transitive information improves accuracy for divergent sequences.

Algorithm selection

MAFFT provides multiple algorithms optimized for different scenarios. Choosing the right one depends on your dataset size and accuracy requirements.

L-INS-i (most accurate)

Uses local pairwise alignment (Smith-Waterman) with iterative refinement. Best for sequences containing a single alignable domain with flanking regions—the flanking sequences are effectively ignored during alignment.

We recommend L-INS-i for datasets under 200 sequences where accuracy is paramount. This is the default for small datasets when using Auto mode.

G-INS-i (global alignment)

Uses global pairwise alignment (Needleman-Wunsch) with iterative refinement. Assumes the entire sequence length should be aligned, making it suitable for full-length protein domains without terminal extensions.

Use G-INS-i when you know your sequences are globally homologous from end to end.

E-INS-i (long gaps)

Uses generalized affine gap costs, allowing long internal gaps without excessive penalty. Designed for sequences with conserved motifs embedded in variable-length regions.

E-INS-i is the most versatile option when you're uncertain about sequence structure. It handles cases where both L-INS-i and G-INS-i might struggle.

FFT-NS-2 (fast)

A progressive method that builds the guide tree twice—once from 6-mer distances, once from the initial alignment. Much faster than iterative methods with reasonable accuracy.

Use FFT-NS-2 for datasets of 500-10,000 sequences where speed matters more than maximum accuracy.

PartTree (very large datasets)

Uses tree-based clustering for initial distance estimation, enabling alignment of tens of thousands of sequences. Accuracy is lower than other methods but computation remains tractable.

Use PartTree only for datasets exceeding 10,000 sequences where other methods are too slow.

Alignment settings

Sequence type

MAFFT auto-detects whether sequences are protein or nucleotide by examining character composition. Manual selection is useful for ambiguous cases like very short sequences.

For nucleotide alignments, MAFFT applies a different scoring matrix optimized for DNA/RNA. The distinction between DNA and RNA affects only the character set validation—alignment scoring is identical.

Output format

- FASTA: Aligned sequences with gaps as

-. Compatible with FastTree and most downstream tools. - Clustal: Traditional format with conservation symbols. Better for visual inspection of alignment quality.

Output order

- Input order: Sequences appear in the same order as your input file. Useful when sequence order is meaningful (e.g., time series samples).

- Aligned order: Sequences are reordered by similarity. Similar sequences appear adjacent, making it easier to spot conserved regions.

Understanding the results

The output alignment shows homologous positions as columns. Gap characters (-) indicate insertions or deletions relative to other sequences.

Alignment length is the total number of columns, which exceeds any individual sequence length due to gaps. A good alignment minimizes scattered gaps and maximizes contiguous aligned blocks.

Conserved columns (identical residues across all sequences) suggest functional importance. Semi-conserved positions (similar amino acids) often indicate structural constraints.

Choosing between MAFFT and Clustal Omega

Both tools produce high-quality alignments, but they excel in different scenarios:

MAFFT's iterative methods (L-INS-i, E-INS-i) generally achieve higher accuracy for difficult alignments with divergent sequences. The FFT-based approach is particularly effective when sequences have variable-length insertions.

Clustal Omega scales better to very large datasets (>10,000 sequences) thanks to its mBed algorithm. Its HMM-based profile alignment can be more robust for sequences with low complexity regions.

For most users with datasets under 1,000 sequences, either tool produces excellent results. We recommend trying both on a subset and comparing the alignments visually.

Common workflows

Multiple sequence alignment is typically the first step in analysis pipelines:

- Phylogenetic analysis: Align with MAFFT → Build tree with FastTree

- Consensus sequence: Align variants → Extract conserved positions

- Structure prediction: Align homologs → Use as input for coevolution-based methods

- Primer design: Align variants → Design primers in conserved regions

Limitations

MAFFT assumes input sequences are homologous. It will produce an alignment for any input, but unrelated sequences yield meaningless results. Verify evolutionary relationships before aligning.

The iterative methods (L-INS-i, G-INS-i, E-INS-i) become slow for datasets exceeding a few hundred sequences. Switch to FFT-NS-2 or PartTree for larger datasets.

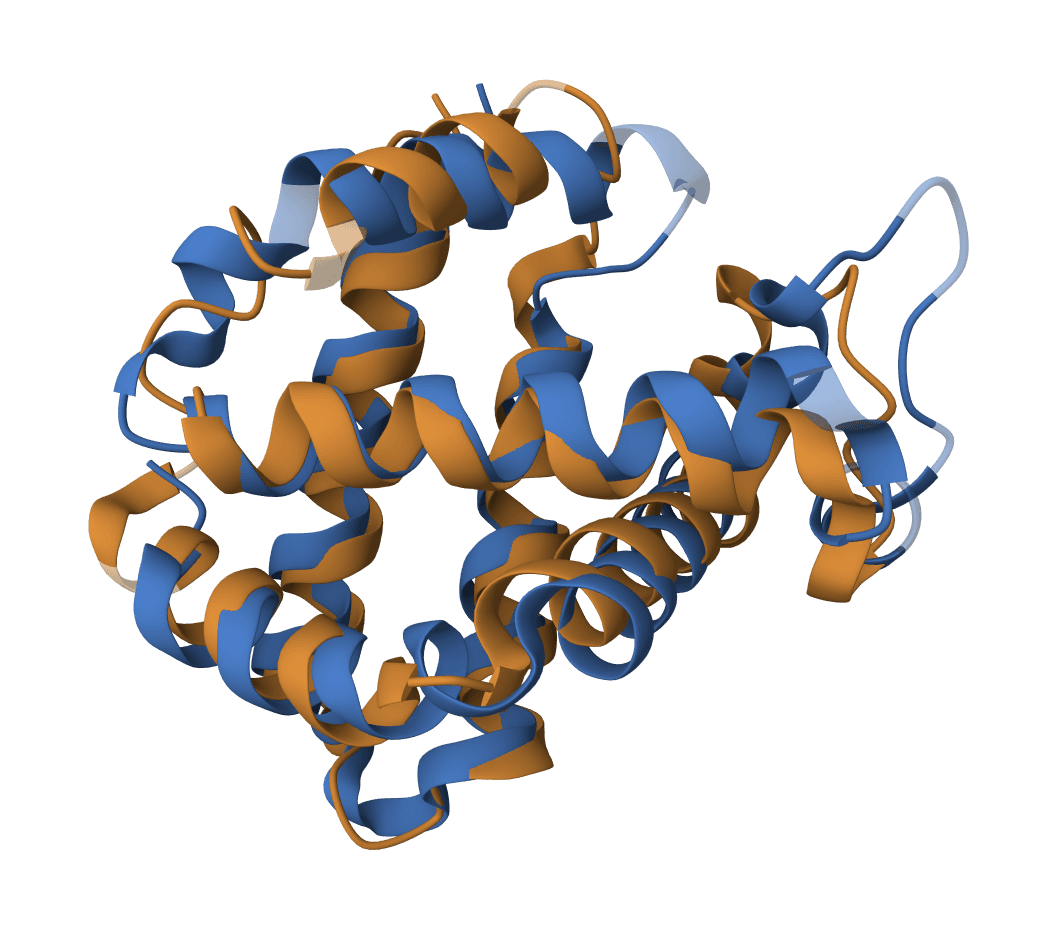

Very divergent sequences (below ~20% identity for proteins) may not align reliably with any sequence-based method. Consider structure-based alignment with USAlign for such cases.

Related tools

- Clustal Omega — Alternative MSA tool with HMM-based profile alignment

- FastTree — Build phylogenetic trees from your alignments

- USAlign — Structure-based alignment when sequences are too divergent

- PDB to FASTA — Extract sequences from structures for alignment